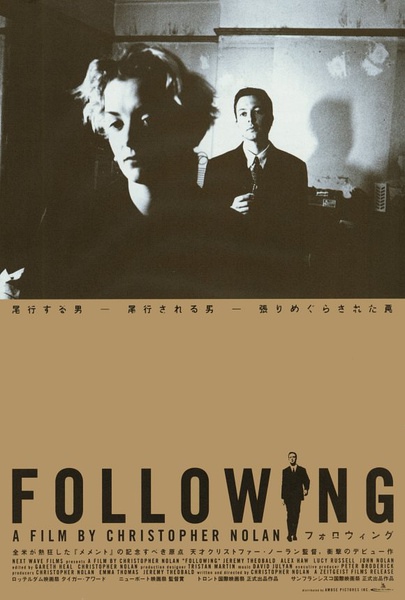

跟踪 Following (1998)

導演: 克里斯多福諾蘭

編劇: 克里斯多福諾蘭

主演: 傑里米·西奧伯德 / 亞歷克斯·霍 / 露西·拉塞爾 / 約翰·諾蘭

類型: 懸疑 / 驚悚 / 犯罪

製片國家/地區: 英國

語言: 英語

上映日期: 1998-09-12(多倫多電影節) / 1999-11-05(英國)

片長: 70分鐘

又名: 致命追踪 / 追隨 / 尾隨

劇情簡介

比爾(Jeremy Theobald飾)是個不成氣候的二流作家,為了增加寫作靈感,每日在街上閒晃,隨機跟蹤觀察陌生人。比爾因而結識了Cobb(Alex Haw飾),並且加入了他闖空門的生意,在他倆四處犯案期間,比爾遇上了一名神秘的金髮美女(Lucy Russell飾),謀殺與金錢等糾葛,讓他陷入無路可退的困境中...。

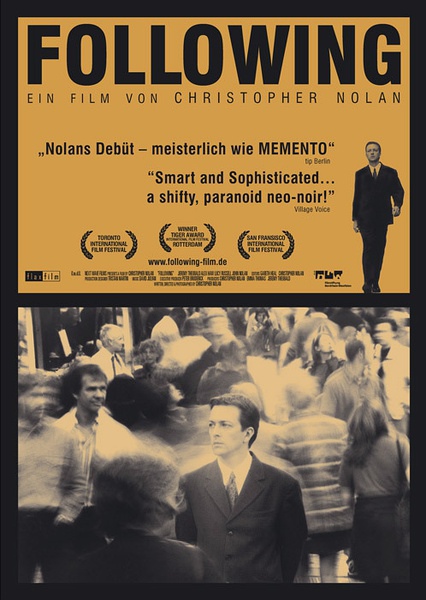

本片是克里斯多福諾蘭(Christopher Nolan)首部編導的黑白劇情長片,獲Newport International Film Festival最佳導演等多個影展四項大獎。

比爾(傑里米•希爾伯德 Jeremy Theobald 飾)是個遊手好閒的作家,借跟踪陌生人打發時間。這讓他體驗到形形色色的人生,很神秘,也很刺激。不過,有一次,比爾盯上了一個西服革履的傢伙克布(艾利克斯•浩爾 Alex Haw 飾)。尾隨到餐廳之後,他卻被對方識破,只得攤牌。克布是個販賣盜版光碟的商販,此外還做擰門撬鎖的勾當。克布帶著比爾潛入了陌生人家中,但比爾發現克布根本不取財物,而是尋找主人蓄意掩蓋的隱私。同時,克布還提醒比爾要注意儀表。後來,比爾認識了一個神秘的金發女人(露西•拉塞爾 Lucy Russell 飾)。在酒吧,比爾主動與她調情,但是對方冷若冰霜。原來她是黑社會大佬的女人,但是不可遏制的激情讓比爾失去了理智,從而墮入了萬劫不復的深淵…

幕後製作

這部不到70分鐘的黑白片,以倒敘作為基本的電影敘事語言,然後在倒敘的基礎上又將時間徹底地敲碎,然後諾蘭將這些時間的碎片粘貼在一起,電影本身的故事並沒有改變,但這樣的拼貼使,於是,這部不到70分鐘的電影有了不可思議的長度。 《跟踪》怀揣著年輕的夢想與野心。

“感謝聖丹斯電影節,我感覺一切彷彿回到昨天一樣。”克里斯托弗·諾蘭一開場就對聖丹斯電影節表達了謝意,因為他的導演處女作《跟踪》(1999)就是在聖丹斯電影節首映,直到今天,諾蘭也忘不了電影節給他提供的展示平台。

克里斯托弗·諾蘭回憶說:“《跟踪》整部電影只用了6000美元完成,但這筆錢也是我當時的全部積蓄,我根本沒有錢來支付演員的費用,所以演職員們大部分都是義務勞動。影片也拍攝了一年多的時間才得以完成。”諾蘭想通過自己的電影經歷告訴年輕的電影人,投資大小並不會妨礙一個電影夢想的實現。

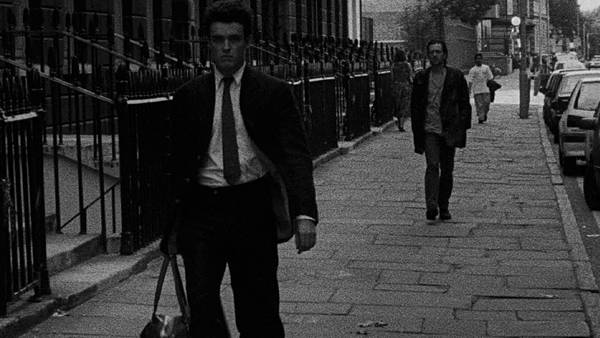

Before he became a sensation with the twisty revenge story Memento, Christopher Nolan fashioned this low-budget, 16 mm black-and-white neonoir with comparable precision and cunning. Providing irrefutable evidence of Nolan’s directorial bravura, Following is the fragmented tale of an unemployed young writer who trails strangers through London, hoping that they will provide inspiration for his first novel. He gets more than he bargained for when one of his unwitting subjects leads him down a dark criminal path. With gritty aesthetics and a made-on-the-fly vibe (many shots were simply stolen on the streets, unbeknownst to passersby), Following is a mind- bending psychological journey that shows the remarkable beginnings of one of today’s most acclaimed filmmakers.

《跟踪》是卓有才華的《黑暗騎士》導演克里斯·諾蘭的第一部劇情長片——剛剛夠得上長片——只有70分鐘。這部影片講的是在倫敦街頭,一個年輕人一時好奇,跟踪起陌生人來,結果不小心被對方發現,從而陷入到悲慘境地之中。諾蘭拍攝《跟踪》,只用了6000美元,可謂一次完美的無成本電影實驗。他把《跟踪》拍成黑白片,既因為製作費太有限,也是基於影片的類型——黑色電影。除了講故事的天份沒法複製,諾蘭拍片時的省錢絕活絕對值得所有為資金所苦的新導演借鑒,包括只用周末時間;大量排練,實拍時一兩條就過,以節約膠片;簡化設備,全部器材可以放到一輛出租車裡;還有隻用自然光;把自己家的房子變成外景地。

作為一部處女作,《跟踪》具有一些令人難以置信的成熟電影技巧,而克里斯·諾蘭使用的非線性敘事技巧,在他之後的影片裡更有變本加厲的勢頭。諾蘭從經典黑色電影中吸取了不少營養,他說:“黑色電影裡,不同角色之間關係的變化總是讓我們重新估量,所以我決定重新設計故事結構,讓每一個新場景的出現都會改變觀眾對影片的理解。”而黑白影像是諾蘭實現這一構想的先決條件。這一招令《洛杉磯時報》的影評人大為讚賞:“(《跟踪》)結構緊湊,是製作精巧的新黑色電影的經典之作。”不難理解,諾蘭在這部影片之後,便步入快車道,進而拍出《記憶碎片》這樣的佳作來。

Repertory Pick: Nolan in Los Angeles

Before he became a Hollywood titan, redefining the contemporary superhero film with his Batman trilogy and creating one of the biggest-budget head trip movies of all time with Inception, Christopher Nolan was an idiosyncratic auteur with limited resources, relying on ingenuity and craft. Tomorrow , his LA fans will have the rare chance to see him speak about his beginnings and his career as a whole, in an event called An Evening with Christopher Nolan, at the Los Angeles Country Museum of Art, following a screening of his microbudget noir debut Following. Watch the original trailer below for the atmospheric and twisty Following, now available from Criterion.

Christopher Nolan, Self-Made Filmmaker

Some directors learn their craft in school. Others acquire skills on the job. Christopher Nolan, who never studied film, seems to just have cinema in his blood. In this clip from a new interview on our special edition release of his debut film, Following , Nolan describes his very early beginnings in the medium and reveals how far resourcefulness and passion can go in getting movies made.

The DIY innovation of Following, a striking psychological noir shot on 16 mm and a shoestring budget, is apparent from its beginning. The film's complex chronology, rhythmic editing, and handheld yet precise camera work demonstrate how technically assured Nolan already was. Watch this extended sequence from the opening, in which the mysterious protagonist starts to give “an account of what happened,” kicking off the film's flashback narrative.

Following: Nolan Begins

By Scott Foundas

“Are you watching closely?” So intones our narrator at the start of Christopher Nolan’s The Prestige, his 2006 tale of rival stage illusionists pursuing a vendetta across decades and continents. But it is a warning that could preface any of Nolan’s eight feature films to date, not least his 1999 Following, a most auspicious debut still little known outside of a small cult of admirers. For Nolan’s work is a reminder that movies evolved not just from photography but also from the world of vaudeville and prestidigitation, where some of the earliest moving-image devices were presented as instruments of magic, and where that “cinemagician” Georges Méliès first honed his craft. Watch closely, for appearances can be—and usually are—deceiving in Nolan’s world, just as time tends to be slippery and narrators less than fully reliable. Watch closely, for Nolan is a master at pulling the rug out from under us, no matter the urgency of our gaze.

There is a wonderful saying, often attributed to that other cinemagician Orson Welles, that the enemy of art is the absence of limitations—and Following is nothing if not an object lesson in this. Shot piecemeal over the course of a year, on black-and-white 16 mm film stock purchased by the twenty-eight-year-old Nolan (who also served as the movie’s cameraman) one roll at a time, Following was produced—by Nolan; his future wife, Emma Thomas; and the film’s star, Jeremy Theobald—for a purported grand total of three thousand pounds, or (by 1998 exchange rates) roughly five thousand dollars, two thousand dollars less than Robert Rodriguez’s El Mariachi (1992) and about twenty thousand less than Kevin Smith’s Clerks (1994). But hey, who’s counting? That thrift is nearly all Nolan’s debut film can be said to have in common with the prevailing indie film scene of the late 1990s, still very much under the influence of the video-store wunderkinder—chiefly Smith and Quentin Tarantino—who infused American movies with a vibrant new strain of pop expressiveness rooted in comic books, seventies exploitation movies, and other assorted “low” art.

Following, by contrast, is a throwback, but decidedly not a pastiche, calling to mind the industrious poverty-row film noirs of the 1940s and ’50s—a movie that might have been exhumed from the vaults of Monogram Pictures (with a lean, seventy-minute running time to boot), or shown on a double bill with another shoestring thriller made by a gifted young director, Stanley Kubrick’s Killer’s Kiss (1955). The primary difference from the latter: whereas Kubrick’s second professional feature (and the first he owned up to) shows flashes of inspiration, compromised by technical problems and a studio-imposed happy ending, Following is that rare debut in which a formidable creative personality seems to have sprung upon the scene fully developed. All of Nolan’s abiding obsessions are in evidence: the boldly nonlinear chronology, the liquid sense of identity, the involuntary spasms of memory. Which, it must be noted, did the film relatively few favors when it was new. Discovered in rough-cut form by the producer and indie-film guru Peter Broderick (who would give Nolan much-needed finishing funds), Following premiered at the 1998 San Francisco Film Festival, went on to screen at Toronto and Slamdance (having been rejected by Sundance), and finally earned a small theatrical release from Zeitgeist Films, during which, despite enthusiastic reviews, it brought in all of fifty thousand dollars. (Fortunately, by then Nolan’s script for Memento had already been optioned, and the rest is history.)

Seen today, Following resembles nothing so much as a first draft of what would eventually become Nolan’s Inception (2010), which is to say, a psychological heist movie in which the most valuable loot exists in the lockbox of the subconscious. In a classic noir setup, the movie begins with our ostensible hero (played by Theobald) in police custody, recounting his lurid tale of woe to an inquisitive detective. The young man, whose name may or may not be Bill (he is credited only as “Young Man”), is an unemployed aspiring writer who has recently taken to “shadowing” random strangers on the streets of London, sampling their lives for a while, searching for inspiration. On one such occasion, he follows his subject long enough to be noticed by him, and the followed man confronts the follower. His name, he says, is Cobb (Alex Haw), and he’s a kind of gentleman burglar—another experiential voyeur, who claims to rob people less for his own benefit than to shake his victims from their complacent consumerism. “You take it away, you show them what they had,” he says, before going on to regale the Young Man with his affinity for the small boxes in which people store not their most valuable possessions but their most personal ones. We are not far here from Inception and its notion that by invading someone’s dreams, one can steal his or her innermost thoughts—a slumbering espionage practiced by another gentleman thief (Leonardo DiCaprio) whose name happens to be Cobb.

The Cobb of Following turns out not to mind being followed, and even entreats the Young Man to continue doing it, to enter into his world—to which the Young Man happily agrees. That is how the Young Man finds himself aiding Cobb in one of his burglaries, of an apartment littered with photographs of a seductive blonde—a Hitchcock blonde—with whom the Young Man becomes smitten. Already a trap has been sprung, but much like the Young Man himself, we are at a loss to say how, why, or to whose ultimate gain. Later, he will seek out this woman (credited as “Blonde” and played by Lucy Russell, the sole member of the primary cast to go on to a sustained acting career), not letting on that they have, in effect, met before. By the time he does this, the Young Man has significantly altered his appearance, not just trimming his straggly hair but trading his threadbare, starving-artist wardrobe for a natty dark suit—a suit rather like the ones favored by Nolan, that rare filmmaker who dresses for the set like a businessman going to the office. And as he changes his clothes, the Young Man changes his demeanor too, becomes surer of himself, becomes almost a different person. It is the first but hardly the last suggestion in Nolan’s work that the clothes really do make the man, whether Batsuit or merely Savile Row.

Few things fascinate Nolan more than the myriad ways in which a given story might be told—the least of them being a straight line. (He has cited the parallel time structures of Graham Swift’s remarkable novel Waterland, read at an impressionable age, as a chief influence in this regard.) In Memento (2000), the action unfolds along two ingeniously reverse-engineered tracks—one moving forward in time and the other backward—all seen through the eyes of a man who has lost the ability to produce new memories. In The Prestige, the shared lives of the two antagonists play out in flashbacks triggered by entries in each man’s diary—diaries written with the full intention of misleading the reader. In Following, Nolan experiments with an even more complex and fragmented structure, dividing the action into four distinct temporalities, circumscribed by a fifth (the police interview), and differentiated by the Young Man’s changing visage: with long hair and short, before and after a violent confrontation that leaves him with a badly swollen eye. Gradually, one strain of the story catches up to another, and the movie’s full jigsaw image begins to take shape. This is how Nolan invades our heads, how he steals our attention.

In lesser hands, such narrative gamesmanship might seem—and often has—little more than elaborate trickery, designed to generate cheap suspense or deflect attention from shortcomings in the script. This may explain why Nolan created an alternate version of the film, reedited in chronological order, as a bonus for an earlier DVD edition (it’s offered on this one as well)—his way of saying to the skeptics in the house, “See, nothing up my sleeves!” In fact, Following works nearly as well played straight as it does all knotted up, perhaps seems even richer in its doomed romanticism. But what that version of Following lacks is its creator’s beautifully articulated feel for the subconscious. Nolan films stories the way we often tell them to one another but rarely see them in the movies—beginning one way, then remembering some crucial omitted detail, doubling back, progressing again, trailing off down a tangential path. And while he is certainly not the only contemporary filmmaker to have sought a cinematic analogue for the workings of the mind—others include David Lynch and the late Raúl Ruiz—few if any have pushed as far in this direction within the parameters of mainstream commercial cinema. When I asked Nolan about this in a 2010 interview pegged to the release of Inception, the biggest-budget head-trip movie ever made in Hollywood, his response was typically coy: “I made a slightly smart-ass crack at somebody the other day because they asked me, ‘What’s your interest in the mind?’ And I said, ‘Well, I’ve lived in one my whole life.’”

To revisit—or discover—Following today is, at least in part, to marvel at how rapidly Nolan has ascended from these humble beginnings to the very top of the big-studio food chain, and how he has managed to do so without compromising his vision. Indeed, he is an anomalous figure: the creator of cerebral blockbusters that make big demands on audiences’ supposedly modest intelligence and ever-dwindling attention span; a stalwart proponent of celluloid in the digital era; and a rather private figure who keeps the precise details of his biography close to the vest. On that last count, it is irresistible to ponder Following as a snapshot of who Nolan himself may have been at that particular moment in his life—perhaps an impressionable young artist seeking experience, perhaps an already keen student of human behavior whose well-laid plans allowed no margin for error. Perhaps a bit of both. Similarly, as Following arrives at its final image, of a scot-free Cobb disappearing into the blur of a crowd, it is tempting to wonder if, perchance, he is vanishing into the recesses of the Young Man’s imagination, from whence he might well have come.

Scott Foundas is associate program director for the Film Society of Lincoln Center, where he also serves as a member of the New York Film Festival Selection Committee and a contributing editor to Film Comment magazine.

留言列表

留言列表